Kategorie

14. Květen 2008

(1850)

DURING A pedestrian trip last summer, through one or two of the

river counties of New York, I found myself, as the day declined,

somewhat embarrassed about the road I was pursuing. The land undulated

very remarkably; and my path, for the last hour, had wound about and

about so confusedly, in its effort to keep in the valleys, that I no

longer knew in what direction lay the sweet village of B-, where I had

determined to stop for the night. The sun had scarcely shone- strictly

speaking- during the day, which nevertheless, had been unpleasantly

warm. A smoky mist, resembling that of the Indian summer, enveloped

all things, and of course, added to my uncertainty. Not that I cared

much about the matter. If I did not hit upon the village before

sunset, or even before dark, it was more than possible that a little

Dutch farmhouse, or something of that kind, would soon make its

appearance- although, in fact, the neighborhood (perhaps on account of

being more picturesque than fertile) was very sparsely inhabited. At

all events, with my knapsack for a pillow, and my hound as a sentry, a

bivouac in the open air was just the thing which would have amused me.

I sauntered on, therefore, quite at ease- Ponto taking charge of my

gun- until at length, just as I had begun to consider whether the

numerous little glades that led hither and thither, were intended to

be paths at all, I was conducted by one of them into an unquestionable

carriage track. There could be no mistaking it. The traces of light

wheels were evident; and although the tall shrubberies and overgrown

undergrowth met overhead, there was no obstruction whatever below,

even to the passage of a Virginian mountain wagon- the most aspiring

vehicle, I take it, of its kind. The road, however, except in being

open through the wood- if wood be not too weighty a name for such an

assemblage of light trees- and except in the particulars of evident

wheel-tracks- bore no resemblance to any road I had before seen. The

tracks of which I speak were but faintly perceptible- having been

impressed upon the firm, yet pleasantly moist surface of- what

looked more like green Genoese velvet than any thing else. It was

grass, clearly- but grass such as we seldom see out of England- so

short, so thick, so even, and so vivid in color. Not a single

impediment lay in the wheel-route- not even a chip or dead twig. The

stones that once obstructed the way had been carefully placed- not

thrown-along the sides of the lane, so as to define its boundaries

at bottom with a kind of half-precise, half-negligent, and wholly

picturesque definition. Clumps of wild flowers grew everywhere,

luxuriantly, in the interspaces.

What to make of all this, of course I knew not. Here was art

undoubtedly- that did not surprise me- all roads, in the ordinary

sense, are works of art; nor can I say that there was much to wonder

at in the mere excess of art manifested; all that seemed to have

been done, might have been done here- with such natural "capabilities"

(as they have it in the books on Landscape Gardening)- with very

little labor and expense. No; it was not the amount but the

character of the art which caused me to take a seat on one of the

blossomy stones and gaze up and down this fairy- like avenue for

half an hour or more in bewildered admiration. One thing became more

and more evident the longer I gazed: an artist, and one with a most

scrupulous eye for form, had superintended all these arrangements. The

greatest care had been taken to preserve a due medium between the neat

and graceful on the one hand, and the pittoresque, in the true sense

of the Italian term, on the other. There were few straight, and no

long uninterrupted lines. The same effect of curvature or of color

appeared twice, usually, but not oftener, at any one point of view.

Everywhere was variety in uniformity. It was a piece of "composition,"

in which the most fastidiously critical taste could scarcely have

suggested an emendation.

I had turned to the right as I entered this road, and now,

arising, I continued in the same direction. The path was so

serpentine, that at no moment could I trace its course for more than

two or three paces in advance. Its character did not undergo any

material change.

Presently the murmur of water fell gently upon my ear- and in a

few moments afterward, as I turned with the road somewhat more

abruptly than hitherto, I became aware that a building of some kind

lay at the foot of a gentle declivity just before me. I could see

nothing distinctly on account of the mist which occupied all the

little valley below. A gentle breeze, however, now arose, as the sun

was about descending; and while I remained standing on the brow of the

slope, the fog gradually became dissipated into wreaths, and so

floated over the scene.

As it came fully into view- thus gradually as I describe it- piece

by piece, here a tree, there a glimpse of water, and here again the

summit of a chimney, I could scarcely help fancying that the whole was

one of the ingenious illusions sometimes exhibited under the name of

"vanishing pictures."

By the time, however, that the fog had thoroughly disappeared, the

sun had made its way down behind the gentle hills, and thence, as it

with a slight chassez to the south, had come again fully into sight,

glaring with a purplish lustre through a chasm that entered the valley

from the west. Suddenly, therefore- and as if by the hand of magic-

this whole valley and every thing in it became brilliantly visible.

The first coup d'oeil, as the sun slid into the position

described, impressed me very much as I have been impressed, when a

boy, by the concluding scene of some well-arranged theatrical

spectacle or melodrama. Not even the monstrosity of color was wanting;

for the sunlight came out through the chasm, tinted all orange and

purple; while the vivid green of the grass in the valley was reflected

more or less upon all objects from the curtain of vapor that still

hung overhead, as if loth to take its total departure from a scene

so enchantingly beautiful.

The little vale into which I thus peered down from under the fog

canopy could not have been more than four hundred yards long; while in

breadth it varied from fifty to one hundred and fifty or perhaps two

hundred. It was most narrow at its northern extremity, opening out

as it tended southwardly, but with no very precise regularity. The

widest portion was within eighty yards of the southern extreme. The

slopes which encompassed the vale could not fairly be called hills,

unless at their northern face. Here a precipitous ledge of granite

arose to a height of some ninety feet; and, as I have mentioned, the

valley at this point was not more than fifty feet wide; but as the

visiter proceeded southwardly from the cliff, he found on his right

hand and on his left, declivities at once less high, less precipitous,

and less rocky. All, in a word, sloped and softened to the south;

and yet the whole vale was engirdled by eminences, more or less

high, except at two points. One of these I have already spoken of.

It lay considerably to the north of west, and was where the setting

sun made its way, as I have before described, into the amphitheatre,

through a cleanly cut natural cleft in the granite embankment; this

fissure might have been ten yards wide at its widest point, so far

as the eye could trace it. It seemed to lead up, up like a natural

causeway, into the recesses of unexplored mountains and forests. The

other opening was directly at the southern end of the vale. Here,

generally, the slopes were nothing more than gentle inclinations,

extending from east to west about one hundred and fifty yards. In

the middle of this extent was a depression, level with the ordinary

floor of the valley. As regards vegetation, as well as in respect to

every thing else, the scene softened and sloped to the south. To the

north- on the craggy precipice- a few paces from the verge- up

sprang the magnificent trunks of numerous hickories, black walnuts,

and chestnuts, interspersed with occasional oak, and the strong

lateral branches thrown out by the walnuts especially, spread far over

the edge of the cliff. Proceeding southwardly, the explorer saw, at

first, the same class of trees, but less and less lofty and

Salvatorish in character; then he saw the gentler elm, succeeded by

the sassafras and locust- these again by the softer linden, red-bud,

catalpa, and maple- these yet again by still more graceful and more

modest varieties. The whole face of the southern declivity was covered

with wild shrubbery alone- an occasional silver willow or white poplar

excepted. In the bottom of the valley itself- (for it must be borne in

mind that the vegetation hitherto mentioned grew only on the cliffs or

hillsides)- were to be seen three insulated trees. One was an elm of

fine size and exquisite form: it stood guard over the southern gate of

the vale. Another was a hickory, much larger than the elm, and

altogether a much finer tree, although both were exceedingly

beautiful: it seemed to have taken charge of the northwestern

entrance, springing from a group of rocks in the very jaws of the

ravine, and throwing its graceful body, at an angle of nearly

forty-five degrees, far out into the sunshine of the amphitheatre.

About thirty yards east of this tree stood, however, the pride of

the valley, and beyond all question the most magnificent tree I have

ever seen, unless, perhaps, among the cypresses of the Itchiatuckanee.

It was a triple- stemmed tulip-tree- the Liriodendron Tulipiferum- one

of the natural order of magnolias. Its three trunks separated from the

parent at about three feet from the soil, and diverging very

slightly and gradually, were not more than four feet apart at the

point where the largest stem shot out into foliage: this was at an

elevation of about eighty feet. The whole height of the principal

division was one hundred and twenty feet. Nothing can surpass in

beauty the form, or the glossy, vivid green of the leaves of the

tulip-tree. In the present instance they were fully eight inches wide;

but their glory was altogether eclipsed by the gorgeous splendor of

the profuse blossoms. Conceive, closely congregated, a million of

the largest and most resplendent tulips! Only thus can the reader

get any idea of the picture I would convey. And then the stately grace

of the clean, delicately- granulated columnar stems, the largest

four feet in diameter, at twenty from the ground. The innumerable

blossoms, mingling with those of other trees scarcely less

beautiful, although infinitely less majestic, filled the valley with

more than Arabian perfumes.

The general floor of the amphitheatre was grass of the same

character as that I had found in the road; if anything, more

deliciously soft, thick, velvety, and miraculously green. It was

hard to conceive how all this beauty had been attained.

I have spoken of two openings into the vale. From the one to the

northwest issued a rivulet, which came, gently murmuring and

slightly foaming, down the ravine, until it dashed against the group

of rocks out of which sprang the insulated hickory. Here, after

encircling the tree, it passed on a little to the north of east,

leaving the tulip tree some twenty feet to the south, and making no

decided alteration in its course until it came near the midway between

the eastern and western boundaries of the valley. At this point, after

a series of sweeps, it turned off at right angles and pursued a

generally southern direction meandering as it went- until it became

lost in a small lake of irregular figure (although roughly oval), that

lay gleaming near the lower extremity of the vale. This lakelet was,

perhaps, a hundred yards in diameter at its widest part. No crystal

could be clearer than its waters. Its bottom, which could be

distinctly seen, consisted altogether, of pebbles brilliantly white.

Its banks, of the emerald grass already described, rounded, rather

than sloped, off into the clear heaven below; and so clear was this

heaven, so perfectly, at times, did it reflect all objects above it,

that where the true bank ended and where the mimic one commenced, it

was a point of no little difficulty to determine. The trout, and

some other varieties of fish, with which this pond seemed to be almost

inconveniently crowded, had all the appearance of veritable

flying-fish. It was almost impossible to believe that they were not

absolutely suspended in the air. A light birch canoe that lay placidly

on the water, was reflected in its minutest fibres with a fidelity

unsurpassed by the most exquisitely polished mirror. A small island,

fairly laughing with flowers in full bloom, and affording little

more space than just enough for a picturesque little building,

seemingly a fowl-house- arose from the lake not far from its

northern shore- to which it was connected by means of an inconceivably

light- looking and yet very primitive bridge. It was formed of a

single, broad and thick plank of the tulip wood. This was forty feet

long, and spanned the interval between shore and shore with a slight

but very perceptible arch, preventing all oscillation. From the

southern extreme of the lake issued a continuation of the rivulet,

which, after meandering for, perhaps, thirty yards, finally passed

through the "depression" (already described) in the middle of the

southern declivity, and tumbling down a sheer precipice of a hundred

feet, made its devious and unnoticed way to the Hudson.

The lake was deep- at some points thirty feet- but the rivulet

seldom exceeded three, while its greatest width was about eight. Its

bottom and banks were as those of the pond- if a defect could have

been attributed, in point of picturesqueness, it was that of excessive

neatness.

The expanse of the green turf was relieved, here and there, by an

occasional showy shrub, such as the hydrangea, or the common snowball,

or the aromatic seringa; or, more frequently, by a clump of

geraniums blossoming gorgeously in great varieties. These latter

grew in pots which were carefully buried in the soil, so as to give

the plants the appearance of being indigenous. Besides all this, the

lawn's velvet was exquisitely spotted with sheep- a considerable flock

of which roamed about the vale, in company with three tamed deer,

and a vast number of brilliantly- plumed ducks. A very large mastiff

seemed to be in vigilant attendance upon these animals, each and all.

Along the eastern and western cliffs- where, toward the upper

portion of the amphitheatre, the boundaries were more or less

precipitous- grew ivy in great profusion- so that only here and

there could even a glimpse of the naked rock be obtained. The northern

precipice, in like manner, was almost entirely clothed by

grape-vines of rare luxuriance; some springing from the soil at the

base of the cliff, and others from ledges on its face.

The slight elevation which formed the lower boundary of this

little domain, was crowned by a neat stone wall, of sufficient

height to prevent the escape of the deer. Nothing of the fence kind

was observable elsewhere; for nowhere else was an artificial enclosure

needed:- any stray sheep, for example, which should attempt to make

its way out of the vale by means of the ravine, would find its

progress arrested, after a few yards' advance, by the precipitous

ledge of rock over which tumbled the cascade that had arrested my

attention as I first drew near the domain. In short, the only

ingress or egress was through a gate occupying a rocky pass in the

road, a few paces below the point at which I stopped to reconnoitre

the scene.

I have described the brook as meandering very irregularly through

the whole of its course. Its two general directions, as I have said,

were first from west to east, and then from north to south. At the

turn, the stream, sweeping backward, made an almost circular loop,

so as to form a peninsula which was very nearly an island, and which

included about the sixteenth of an acre. On this peninsula stood a

dwelling-house- and when I say that this house, like the infernal

terrace seen by Vathek, "etait d'une architecture inconnue dans les

annales de la terre," I mean, merely, that its tout ensemble struck me

with the keenest sense of combined novelty and propriety- in a word,

of poetry- (for, than in the words just employed, I could scarcely

give, of poetry in the abstract, a more rigorous definition)- and I do

not mean that merely outre was perceptible in any respect.

In fact nothing could well be more simple- more utterly unpretending

than this cottage. Its marvellous effect lay altogether in its

artistic arrangement as a picture. I could have fancied, while I

looked at it, that some eminent landscape-painter had built it with

his brush.

The point of view from which I first saw the valley, was not

altogether, although it was nearly, the best point from which to

survey the house. I will therefore describe it as I afterwards saw it-

from a position on the stone wall at the southern extreme of the

amphitheatre.

The main building was about twenty-four feet long and sixteen broad-

certainly not more. Its total height, from the ground to the apex of

the roof, could not have exceeded eighteen feet. To the west end of

this structure was attached one about a third smaller in all its

proportions:- the line of its front standing back about two yards from

that of the larger house, and the line of its roof, of course, being

considerably depressed below that of the roof adjoining. At right

angles to these buildings, and from the rear of the main one- not

exactly in the middle- extended a third compartment, very small-

being, in general, one-third less than the western wing. The roofs

of the two larger were very steep- sweeping down from the ridge-beam

with a long concave curve, and extending at least four feet beyond the

walls in front, so as to form the roofs of two piazzas. These latter

roofs, of course, needed no support; but as they had the air of

needing it, slight and perfectly plain pillars were inserted at the

corners alone. The roof of the northern wing was merely an extension

of a portion of the main roof. Between the chief building and

western wing arose a very tall and rather slender square chimney of

hard Dutch bricks, alternately black and red:- a slight cornice of

projecting bricks at the top. Over the gables the roofs also projected

very much:- in the main building about four feet to the east and two

to the west. The principal door was not exactly in the main

division, being a little to the east- while the two windows were to

the west. These latter did not extend to the floor, but were much

longer and narrower than usual- they had single shutters like doors-

the panes were of lozenge form, but quite large. The door itself had

its upper half of glass, also in lozenge panes- a movable shutter

secured it at night. The door to the west wing was in its gable, and

quite simple- a single window looked out to the south. There was no

external door to the north wing, and it also had only one window to

the east.

The blank wall of the eastern gable was relieved by stairs (with a

balustrade) running diagonally across it- the ascent being from the

south. Under cover of the widely projecting eave these steps gave

access to a door leading to the garret, or rather loft- for it was

lighted only by a single window to the north, and seemed to have

been intended as a store-room.

The piazzas of the main building and western wing had no floors,

as is usual; but at the doors and at each window, large, flat

irregular slabs of granite lay imbedded in the delicious turf,

affording comfortable footing in all weather. Excellent paths of the

same material- not nicely adapted, but with the velvety sod filling

frequent intervals between the stones, led hither and thither from the

house, to a crystal spring about five paces off, to the road, or to

one or two out- houses that lay to the north, beyond the brook, and

were thoroughly concealed by a few locusts and catalpas.

Not more than six steps from the main door of the cottage stood

the dead trunk of a fantastic pear-tree, so clothed from head to

foot in the gorgeous bignonia blossoms that one required no little

scrutiny to determine what manner of sweet thing it could be. From

various arms of this tree hung cages of different kinds. In one, a

large wicker cylinder with a ring at top, revelled a mocking bird;

in another an oriole; in a third the impudent bobolink- while three or

four more delicate prisons were loudly vocal with canaries.

The pillars of the piazza were enwreathed in jasmine and sweet

honeysuckle; while from the angle formed by the main structure and its

west wing, in front, sprang a grape-vine of unexampled luxuriance.

Scorning all restraint, it had clambered first to the lower roof- then

to the higher; and along the ridge of this latter it continued to

writhe on, throwing out tendrils to the right and left, until at

length it fairly attained the east gable, and fell trailing over the

stairs.

The whole house, with its wings, was constructed of the

old-fashioned Dutch shingles- broad, and with unrounded corners. It is

a peculiarity of this material to give houses built of it the

appearance of being wider at bottom than at top- after the manner of

Egyptian architecture; and in the present instance, this exceedingly

picturesque effect was aided by numerous pots of gorgeous flowers that

almost encompassed the base of the buildings.

The shingles were painted a dull gray; and the happiness with

which this neutral tint melted into the vivid green of the tulip

tree leaves that partially overshadowed the cottage, can readily be

conceived by an artist.

From the position near the stone wall, as described, the buildings

were seen at great advantage- for the southeastern angle was thrown

forward- so that the eye took in at once the whole of the two

fronts, with the picturesque eastern gable, and at the same time

obtained just a sufficient glimpse of the northern wing, with parts of

a pretty roof to the spring-house, and nearly half of a light bridge

that spanned the brook in the near vicinity of the main buildings.

I did not remain very long on the brow of the hill, although long

enough to make a thorough survey of the scene at my feet. It was clear

that I had wandered from the road to the village, and I had thus

good traveller's excuse to open the gate before me, and inquire my

way, at all events; so, without more ado, I proceeded.

The road, after passing the gate, seemed to lie upon a natural

ledge, sloping gradually down along the face of the north-eastern

cliffs. It led me on to the foot of the northern precipice, and thence

over the bridge, round by the eastern gable to the front door. In this

progress, I took notice that no sight of the out-houses could be

obtained.

As I turned the corner of the gable, the mastiff bounded towards

me in stern silence, but with the eye and the whole air of a tiger.

I held him out my hand, however, in token of amity- and I never yet

knew the dog who was proof against such an appeal to his courtesy.

He not only shut his mouth and wagged his tail, but absolutely offered

me his paw-afterward extending his civilities to Ponto.

As no bell was discernible, I rapped with my stick against the door,

which stood half open. Instantly a figure advanced to the threshold-

that of a young woman about twenty-eight years of age- slender, or

rather slight, and somewhat above the medium height. As she

approached, with a certain modest decision of step altogether

indescribable. I said to myself, "Surely here I have found the

perfection of natural, in contradistinction from artificial grace."

The second impression which she made on me, but by far the more

vivid of the two, was that of enthusiasm. So intense an expression

of romance, perhaps I should call it, or of unworldliness, as that

which gleamed from her deep-set eyes, had never so sunk into my

heart of hearts before. I know not how it is, but this peculiar

expression of the eye, wreathing itself occasionally into the lips, is

the most powerful, if not absolutely the sole spell, which rivets my

interest in woman. "Romance, provided my readers fully comprehended

what I would here imply by the word- "romance" and "womanliness"

seem to me convertible terms: and, after all, what man truly loves

in woman, is simply her womanhood. The eyes of Annie (I heard some one

from the interior call her "Annie, darling!") were "spiritual grey;"

her hair, a light chestnut: this is all I had time to observe of her.

At her most courteous of invitations, I entered- passing first

into a tolerably wide vestibule. Having come mainly to observe, I took

notice that to my right as I stepped in, was a window, such as those

in front of the house; to the left, a door leading into the

principal room; while, opposite me, an open door enabled me to see a

small apartment, just the size of the vestibule, arranged as a

study, and having a large bow window looking out to the north.

Passing into the parlor, I found myself with Mr. Landor- for this, I

afterwards found, was his name. He was civil, even cordial in his

manner, but just then, I was more intent on observing the arrangements

of the dwelling which had so much interested me, than the personal

appearance of the tenant.

The north wing, I now saw, was a bed-chamber, its door opened into

the parlor. West of this door was a single window, looking toward

the brook. At the west end of the parlor, were a fireplace, and a door

leading into the west wing- probably a kitchen.

Nothing could be more rigorously simple than the furniture of the

parlor. On the floor was an ingrain carpet, of excellent texture- a

white ground, spotted with small circular green figures. At the

windows were curtains of snowy white jaconet muslin: they were

tolerably full, and hung decisively, perhaps rather formally in sharp,

parallel plaits to the floor- just to the floor. The walls were

prepared with a French paper of great delicacy, a silver ground,

with a faint green cord running zig-zag throughout. Its expanse was

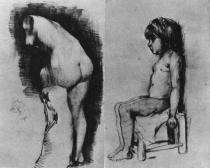

relieved merely by three of Julien's exquisite lithographs a trois

crayons, fastened to the wall without frames. One of these drawings

was a scene of Oriental luxury, or rather voluptuousness; another

was a "carnival piece," spirited beyond compare; the third was a Greek

female head- a face so divinely beautiful, and yet of an expression so

provokingly indeterminate, never before arrested my attention.

The more substantial furniture consisted of a round table, a few

chairs (including a large rocking-chair), and a sofa, or rather

"settee;" its material was plain maple painted a creamy white,

slightly interstriped with green; the seat of cane. The chairs and

table were "to match," but the forms of all had evidently been

designed by the same brain which planned "the grounds;" it is

impossible to conceive anything more graceful.

On the table were a few books, a large, square, crystal bottle of

some novel perfume, a plain ground- glass astral (not solar) lamp with

an Italian shade, and a large vase of resplendently-blooming

flowers. Flowers, indeed, of gorgeous colours and delicate odour

formed the sole mere decoration of the apartment. The fire-place was

nearly filled with a vase of brilliant geranium. On a triangular shelf

in each angle of the room stood also a similar vase, varied only as to

its lovely contents. One or two smaller bouquets adorned the mantel,

and late violets clustered about the open windows.

It is not the purpose of this work to do more than give in detail, a

picture of Mr. Landor's residence- as I found it. How he made it

what it was- and why- with some particulars of Mr. Landor himself-

may, possibly form the subject of another article.